Pintele Part 1: Straight Outta Anatevka

We begin with the story of how I found my identity in great American musicals. Then we return to the Pale of Settlement, follow my great grandmother across the ocean, and begin to explore the relationship between Judaism and Jewishness, as represented by her two daughters.

Listen now: Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Amazon Music Podcasts | YouTube | YouTube Music Podcasts | Pandora | iHeart Radio | Podbean | rss.com | Listen Notes | Podchaser | and more

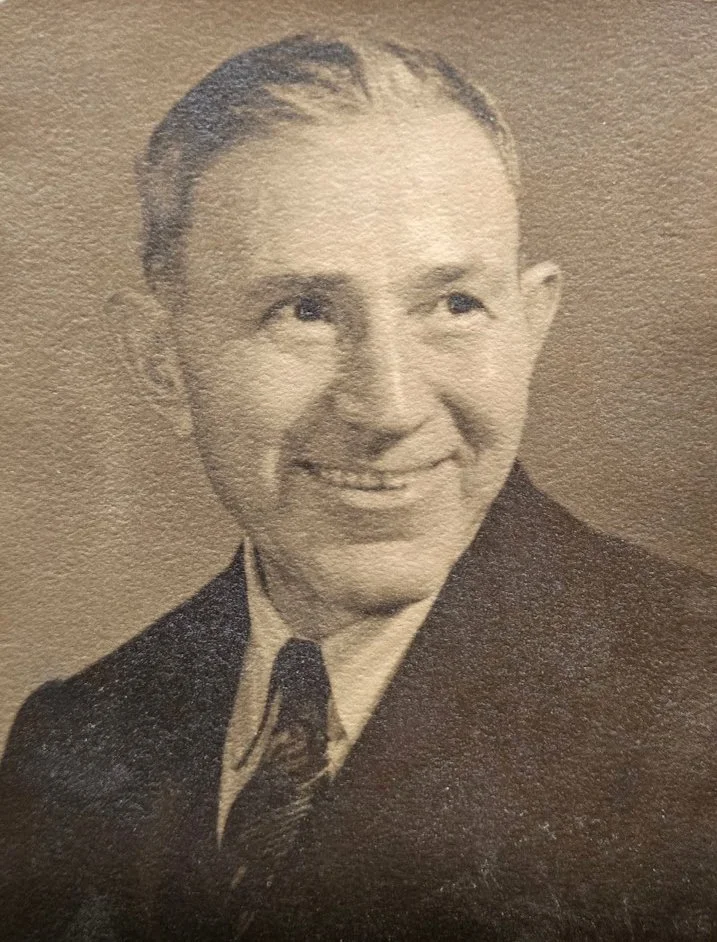

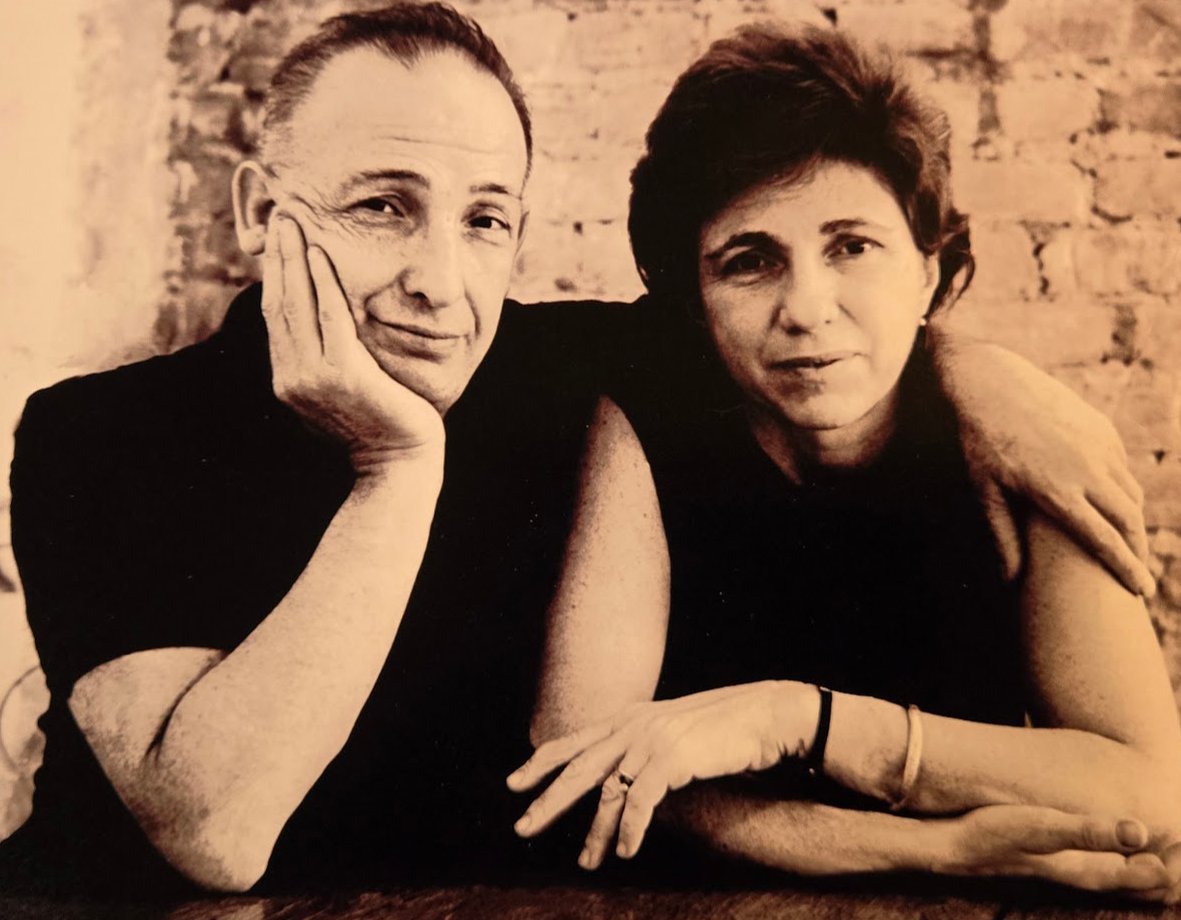

Schmuel Axelrod and Dalia Miriam Michnowitz

Welcome, and if you’ve listened to the first chapter of Pintele, thanks for listening! These episode pages will serve as endnotes, with links to source material, pictures, and other possibly interesting things. There’s a comments section below, where I invite you to share your thoughts after you’ve listened to the episode. Now on with the notes!

There are many official photos of the performance of 1776 at the Nixon White House in 1970; this is my favorite, as discussed in Pintele 1. You might be interested in the Times’ coverage of the event. If you’re a big 1776 fan you’re familiar with Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards’ wonderful “Historical Note by the Authors.” Some early listeners to this chapter have asked what I mean when I say that William Daniels “talked like a black Trans Am.”

The Howard Da Silva-curious can read Trav S.D. on Da Silva; watch Cladrite Radio’s “Ten Things You Should Know About Howard Da Silva”; then take a break, maybe have a bite to eat; and read the Times’ coverage of Da Silva’s refusal to cooperate with HUAC in 1951.

George Washington’s “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance” is from his August 18, 1790 letter to the Touro Synagogue. John Adams’ “not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion” is from the May 26, 1797 Treaty of Tripoli.

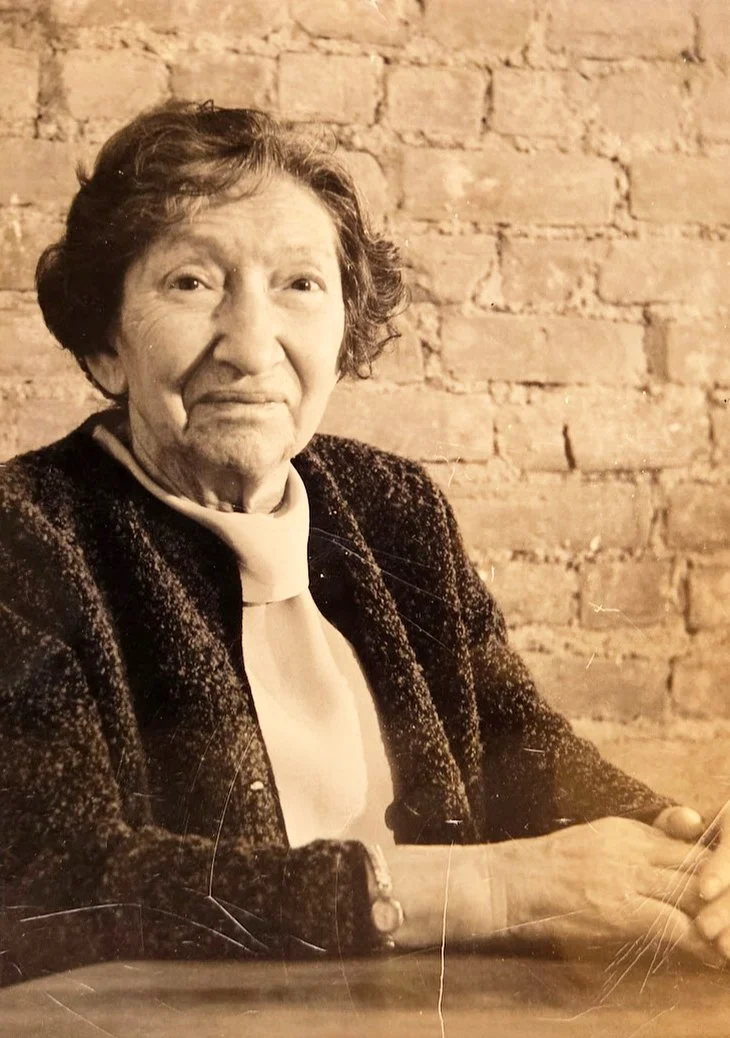

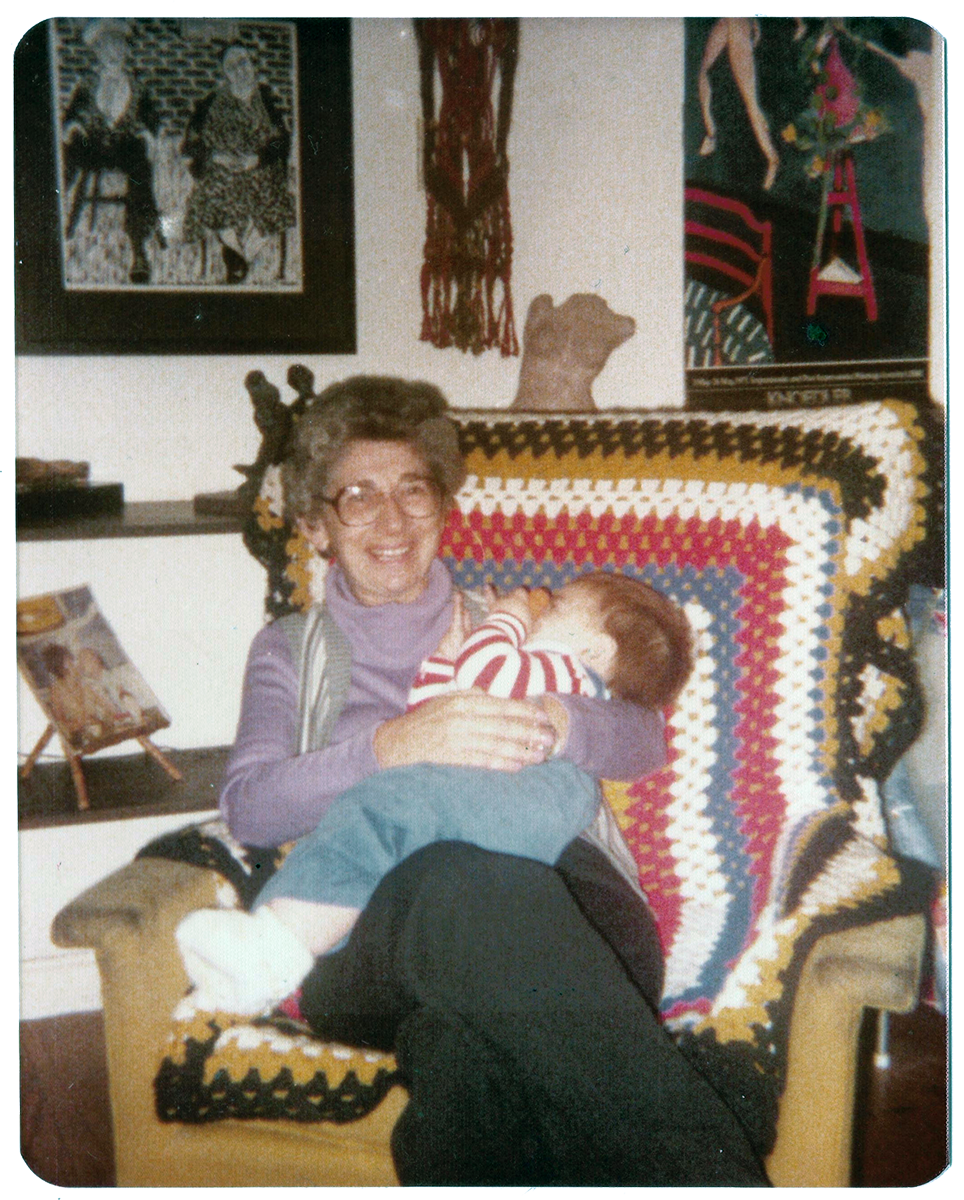

Jennie and her daughters: Estelle (Red), Sarah, and Jennie Ragovin, late 1940s

Thoughts on Zora Neale Hurston’s analysis of Jewish history, including the passage quoted in Pintele, can be found in “Why Zora Neale Hurston Was Obsessed with the Jews,” Louis Menand, The New Yorker, January 13, 2025.

You can see Jerome Robbins’ Broadway excerpts from the 1989 Tony Awards; and look at this beautiful photo of the Imperial Theatre marquee during the run! While you’re in the neighborhood, you can watch Jason Alexander collect his Tony, and you can hear some of his performance on the cast recording. As for Zero Mostel, there’s not much available film of him as Tevye, but here are a couple of minutes, and here he is doing “If I Were a Rich Man” at the 1965 Tonys. He’s also on the definitive original cast recording.

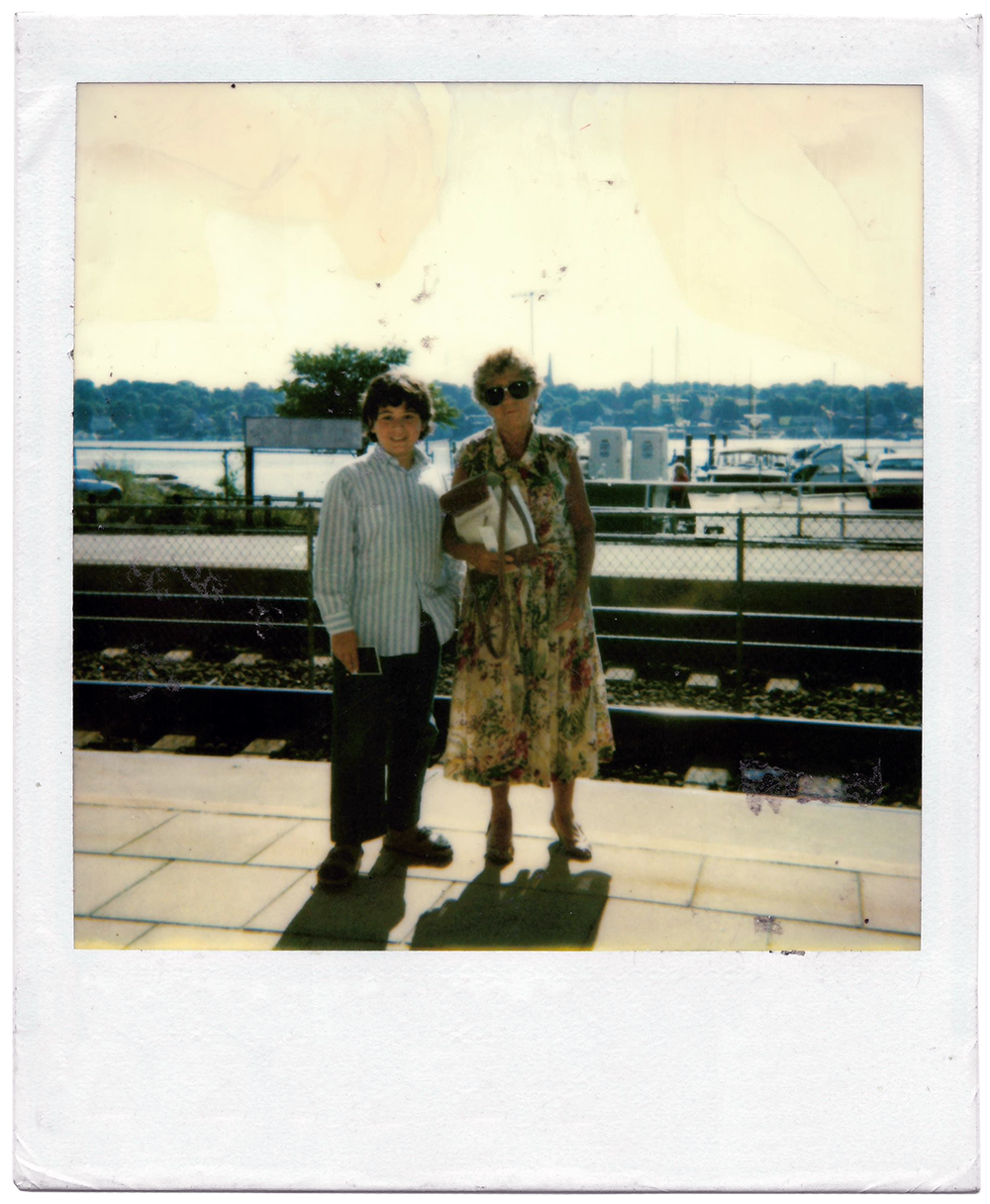

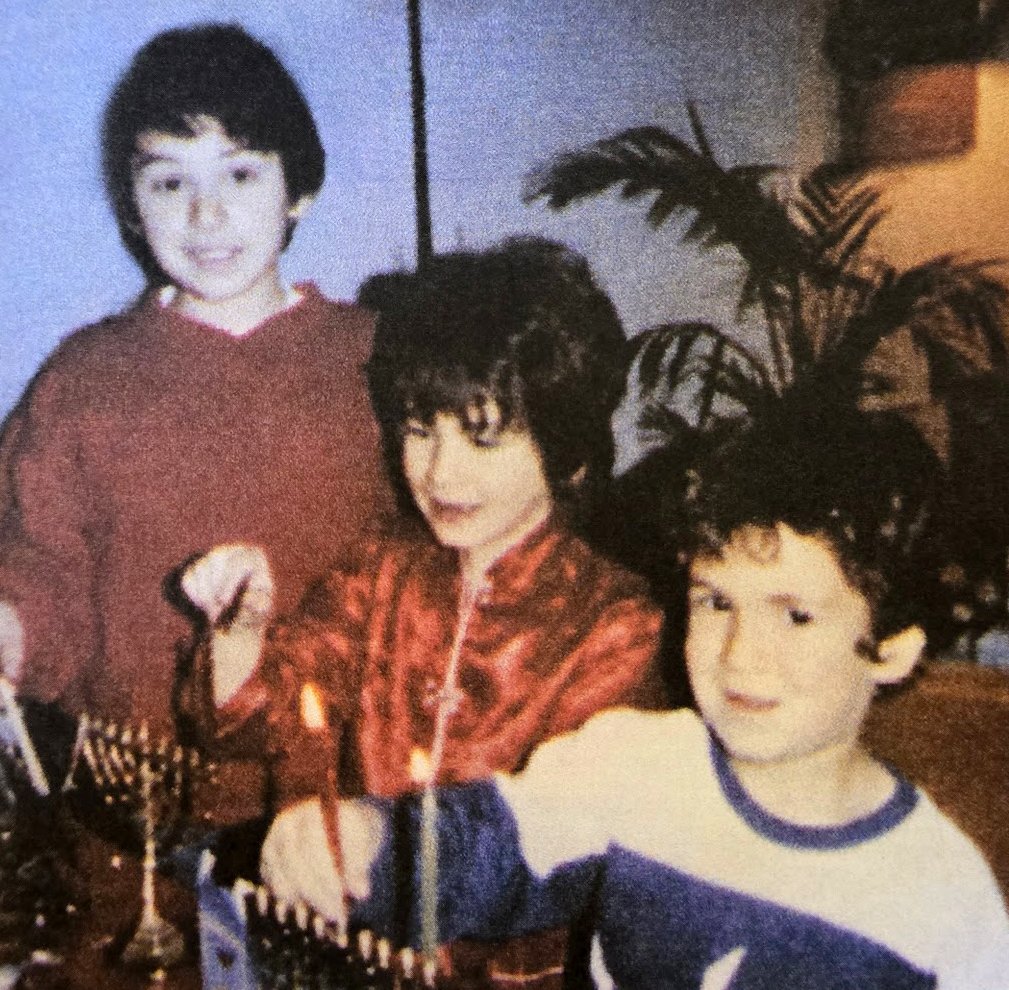

With Grandma Red in New London, Connecticut, waiting for the train to New York City, 1989. Photo by my cousin Josh.

Regarding Fiddler, its creation, and its ongoing history, Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof by Alisa Solomon is indispensable. Max Lewkowicz’s documentary Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles is highly recommended, and for valuable perspective on the film version, see Zack Paslay’s Fiddler on the Roof’s Place in the New Hollywood. The original Tevye stories by Sholom Aleichem exist in many translations and compilations; the version translated by Frances Butwin and originally published in 1949 as Tevye’s Daughters seems to be the one Bock, Harnick, Stein, and Robbins were working from. Anyone interested in the genesis of the score of Fiddler absolutely must experience Bock to Harnick: Composing the Score to Fiddler on the Roof, an astonishing collection of working demos, released in 2015 and available on Bandcamp. You also might enjoy Frank Jacobs and Mort Drucker’s Antenna on the Roof, which first appeared in Mad #156 (January 1973), and has been reprinted elsewhere, including in The Big Book of Jewish Humor. We’ll return to Anatevka in Pintele 4.

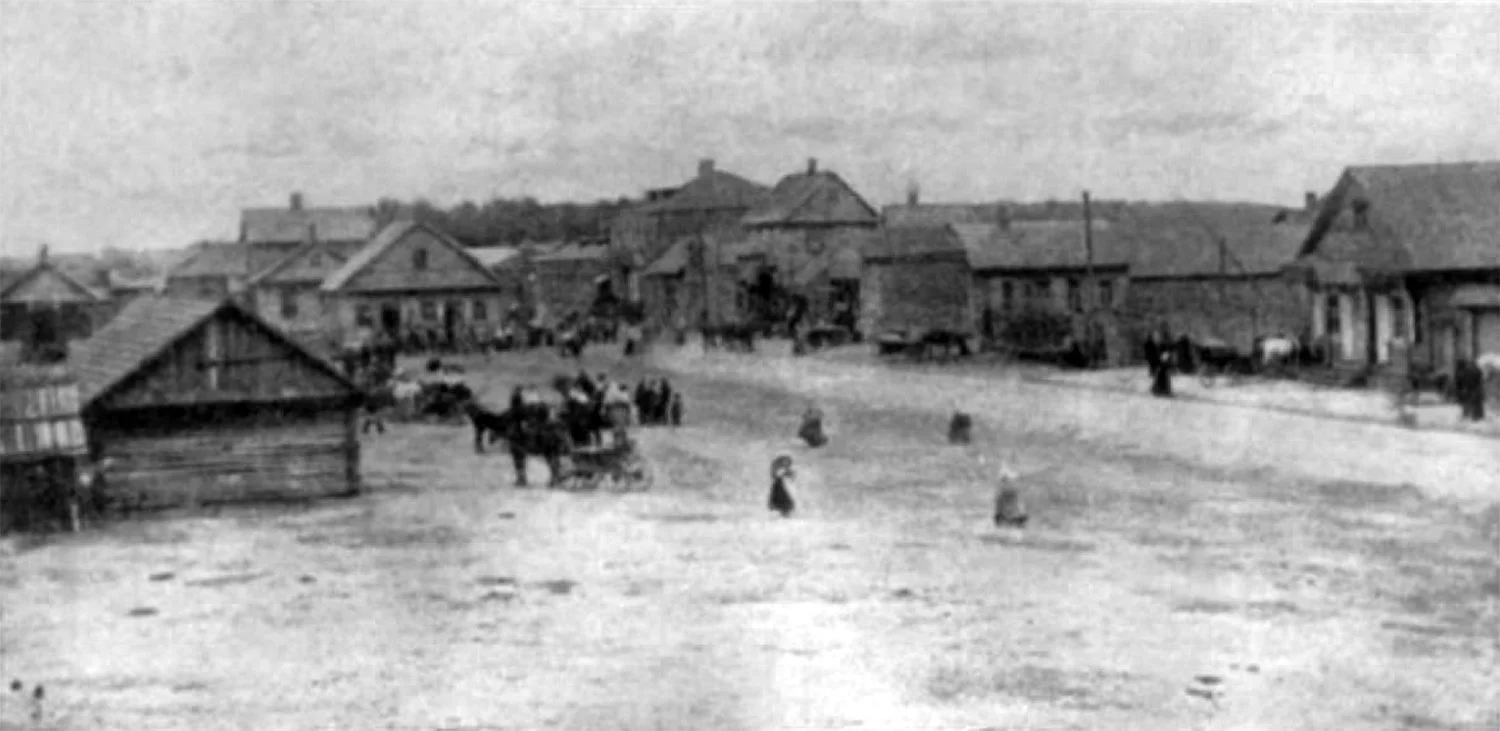

Sources for impressions of shtetl life include Life is with People by Mark Zborowski and Elizabeth Herzog; this essay by Samuel Kassow for the YIVO Encyclopedia; an unpublished memoir by my relative Meir Axelrod; and the photographs of Roman Vishniac, as published in A Vanished World.

Eilat Gordin Levitan’s website has a great deal of information about the Jewish history of Molodechno, though apparently nothing specific about Grandma Jennie’s family, other than some mentions of Mordechai Berman. Berman lived in Molodechno and later married Sarah Axelrod (daughter of Meir and Sonia, sister of Sam, best friend of Esther) in Tel Aviv in the early 1940s. (The Axelrod family discussed on Levitan’s site, including the painter Meer Akselrod aka Meir Axelrod, apparently have no relation to our Axelrods. This could be one reason why many members of Jennie’s family, including Jennie herself, sometimes used the alternate surname Gershon. I didn’t mention this in Pintele because I thought the story’s abundance of Sarahs and Esthers was confusing enough already.) Additional background comes from The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust. All quotes from Sam Axelrod are from his 2002 memoir The Wolf and the Lamb. Wilma Bulkin Siegel painted an evocative watercolor portrait of Sam in 2005.

Falek (sometimes Falik or Falk) Zolf is quoted from On Foreign Soil: Tales of a Wandering Jew, which provides rich, occasionally heartbreaking detail about Molodechno and the surrounding area not long after Jennie left for America. It’s likely that Jennie’s family knew Zolf’s uncle, Menachem Dolinski, a cantor and a butcher.

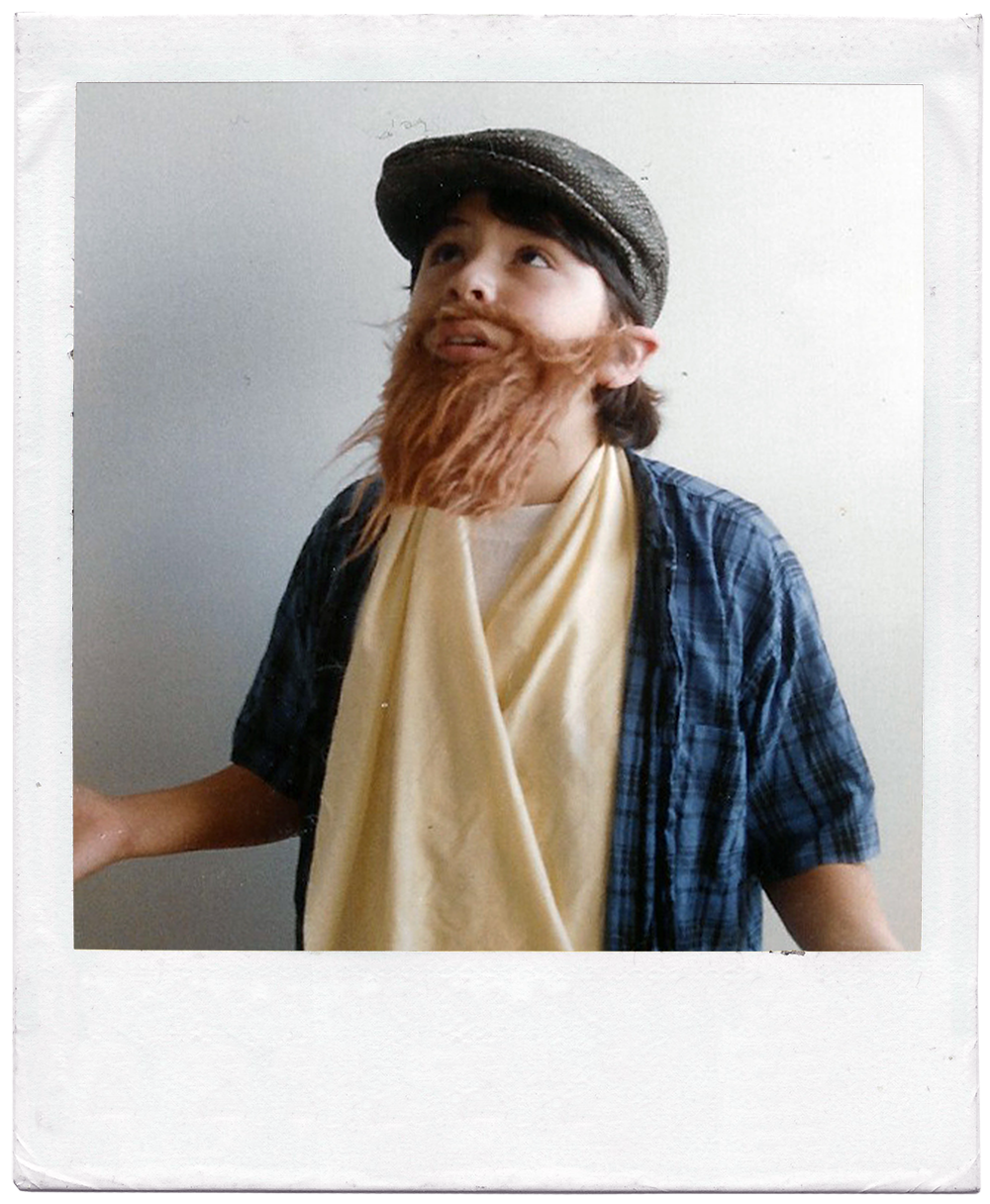

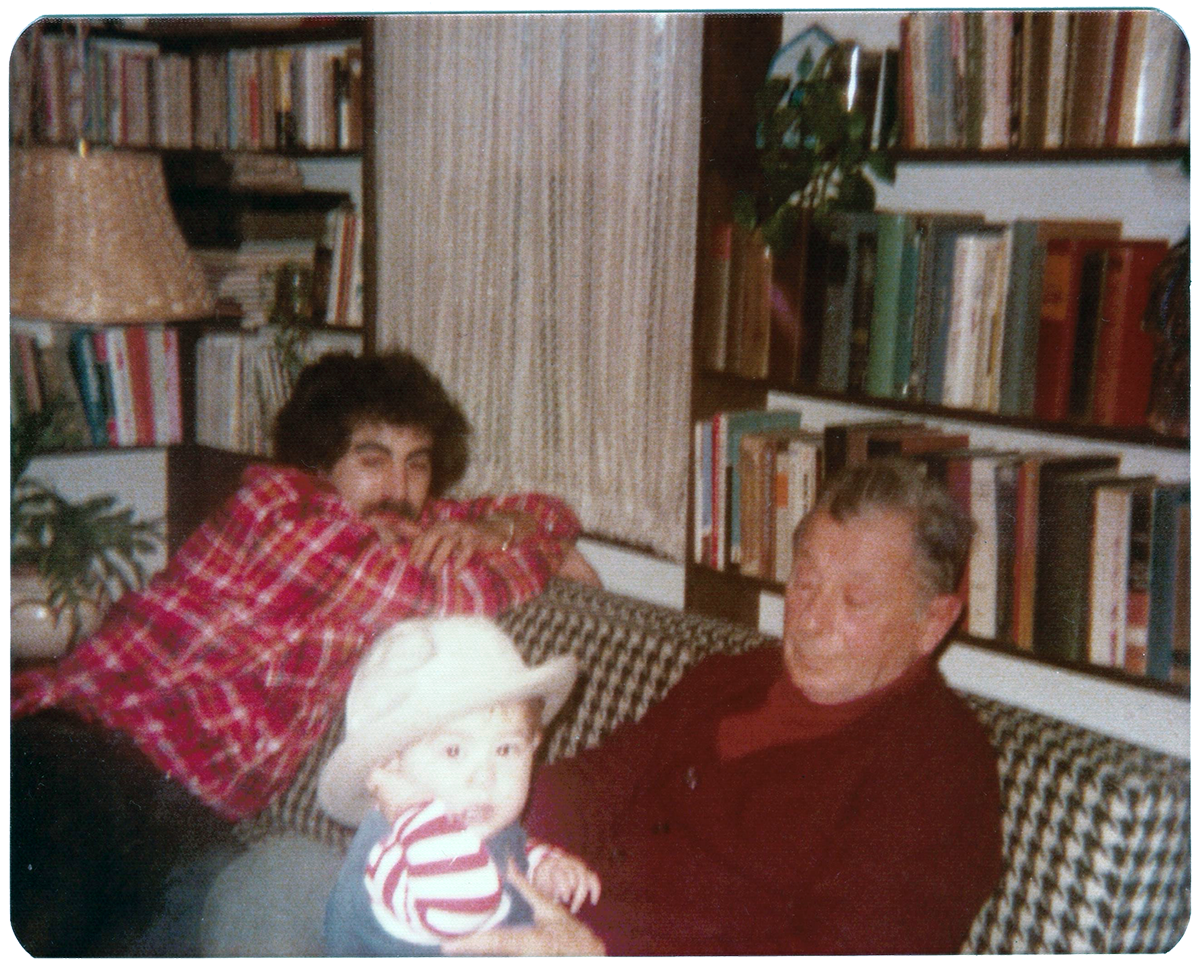

A twelve-year-old Tevye, 1989

There are photos of modern-day Molodechno here, here, and here.

Mark Twain offers graphic descriptions of Russian pogrom violence against Jews in Part Three of his 1906 “Reflections on Religion,” and angrily denounces “the ultra-Christian Government of Russia,” practicing “the one and only religion of peace and love,” which “has been officially ordering and conducting massacres of its Jewish subjects.”

Impressions of Joshua “Kurtzefraytik” Axelrod are from Meir’s unpublished memoir. Special thanks to my cousin Michael Axelrod for providing valuable insight, as well as additional excerpts from Meir’s writing. Impressions of Esther Axelrod are from Sam Axelrod, The Wolf and the Lamb.

The 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, signed into law by Republican President Calvin Coolidge, was an invaluable tool in helping the Nazis murder thirteen million people.

Details of the mass killing in Molodechno are from The Wolf and the Lamb. Other details are from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, Volume II. Quoted descriptions and details from similar accounts of similar massacres are from The New York Times, June 16, 1942; Star Weekly, August 15, 1942; The Buffalo Jewish Review, August 21, 1942; United Press, London, October 1, 1942; The Patterson News, November 28, 1942; and The Holocaust by Martin Gilbert. The Inter-Allied Information Committee is quoted from the Associated Press, London, December 20, 1942.

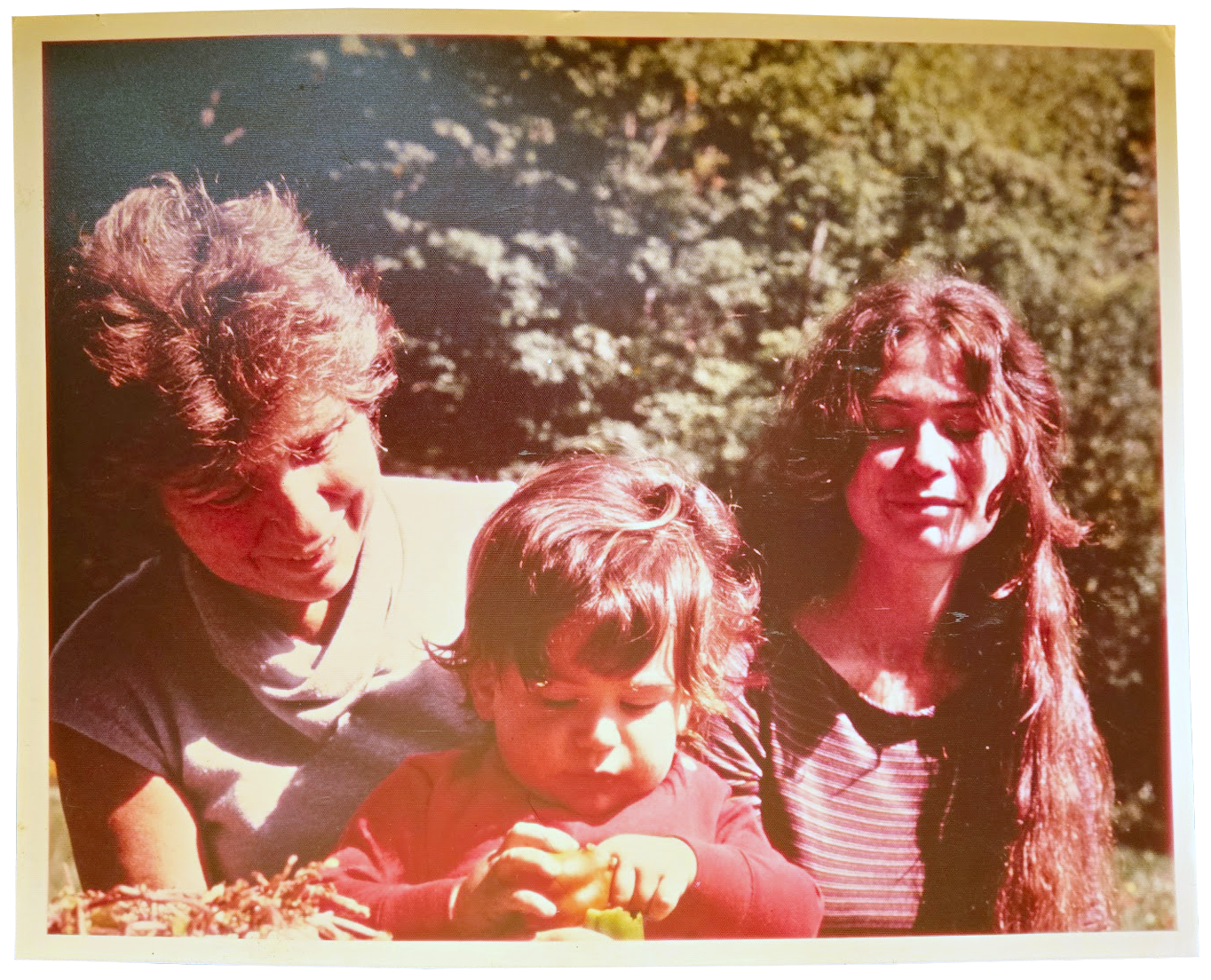

Cousins Sarah Axelrod and Esther Axelrod in Tel Aviv, late 1930s. This photo, like some others on this page, belonged to Grandma Red, who in addition to many wonderful qualities, had a maddening habit of cutting photographs into little circles.

In his book, Sam describes his 1997 visit to Molodechno, where he met a man who claimed to have witnessed the massacre. He tells Sam that the Nazis involved were not actually German soldiers, but fascist mercenaries from Lithuania, working on behalf of Germany. I haven’t confirmed this, and I omitted it from the episode for the sake of clarity. It does appear in the testimonies Sam provided for Esther; her sisters, Sonya, Dina, Miriam, and Chana; and her parents, Rachel Spector and Joshua Axelrod; to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, in 2008.

It’s worth learning about Rabbi Bernard Moses Casper and author/journalist Meyer Levin, both of whom crossed Aunt Sarah’s path at key moments during her military service. It’s also worth looking at newsreel footage showing the rededication of the Metz Synagogue, the event Sarah had planned to attend.

Ashrita Furman holds the Guinness World Record for holding the most Guinness World Records. The record Grandma Red, Josh, and I witnessed him setting at the Empire State Building in 1989 (juggling on a pogo stick) has since been broken — also by Ashrita Furman. Sadly, the Stage Deli closed in 2012, and the Carnegie Deli in 2016. Woody Allen’s response to the “self-hating Jew” smear (“I may hate myself, but not ‘cause I’m Jewish”) is from this scene in Deconstructing Harry (1997).

Eleanor Reissa’s recording of “Yankee Doodle Boy / Lebn Zol Columbus,” from her 1992 album Going Home: Gems of Yiddish Song, is used with her generous permission. Eleanor Reissa is an accomplished playwright and actor, Tony Award-nominated director, international concert artist, and much more. I strongly recommend Going Home and Songs in the Key of Yiddish, as well as the extraordinary 2022 book The Letters Project: A Daughter’s Journey. The audiobook, read by the author, is especially worthwhile, and it was a source of inspiration as I worked on Pintele 1. Learn more at eleanorreissa.com.

You can learn more about the song “Lebn Zol Columbus,” including lyrics in Yiddish and English, from the Milken Archive of Jewish Music and the Yosl and Chana Mlotek Yiddish Song Collection. Musical theatre fans will note that the lines “A shtetl iz amerike / A mekhaye, khlebn” are quoted in Lynne Ahrens’ lyrics for Ragtime. It means “America is a shtetl / where I swear life is great.”

Aunt Sarah and Uncle Joe will return in Pintele 3: A Very Brody Passover.